His reforms were widespread, both at a symbolic level and in terms of political and economic reforms. For one, in 1984 he changed the country’s name from Upper Volta, the name it kept from colonialism, to Burkina Faso. The country’s new name translates as “the land of the upright people.”

Sankara preached economic self-reliance. He shunned World Bank loans and promoted local food and textile production. (There’s a classic scene in Shuffield’s documentary where he had the whole Burkina delegation to an Organization of African Unity meeting decked out in local textiles and designs.)

Sankara outlawed tribute payments and obligatory labour to village chiefs, abolished rural poll taxes, instituted a massive immunization program, built railways and kick-started public housing construction. His administration aggressively pushed literacy programs, tackled river blindness and embarked on an anti-corruption drive in the civil service.

Women, the poor and the country’s peasantry benefited mostly from these reforms. His administration promoted gender equality in a very male-dominated society (including outlawing female circumcision and polygamy). As Sankara told a local audience in 1984: “Socially, [women] are relegated to third place, after the man and the child — just like the Third World, arbitrarily held back, the better to be dominated and exploited.”

He discouraged the luxuries that came with government office and encouraged others to do the same. He earned a small salary ($450 a month), refused to have his picture displayed in public buildings, and forbade the uses of chauffeur-driven Mercedes and first class airline tickets by his ministers and senior civil servants.

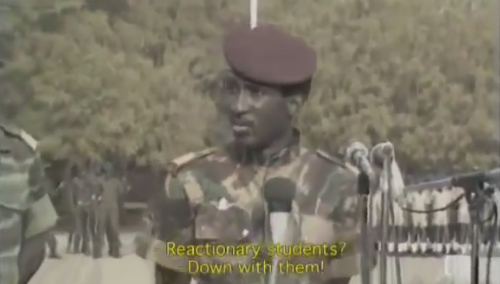

But Sankara’s regime was not immune to undemocratic practices.

He banned trade unions and political parties, and put down protests (most significantly one by teachers in 1986). Many people were the victims of summary judgments by people’s revolutionary tribunals, which sentenced “lazy workers,” “counter-revolutionaries” and corrupt officials. Sankara himself would later admit on camera that the tribunals were often used as occasions to settle private scores.

By 1987, he was politically isolated. His enemies – a mix of the French political establishment (he had humiliated President François Mitterand in public on a few occasions) and regional leaders (like Ivorian President Félix Houphouët-Boigny) – began to tire of him.

Compaoré is widely suspected to have ordered Sankara’s murder in order to do the French and regional dictators a favor. Though Compaoré pretended to publicly grieve for Sankara and promised to preserve his legacy, he quickly set about purging the government of Sankara supporters.

In contrast to the cool reception given Sankara earlier, Compaoré was welcomed by Western governments and funding agencies. Within three years, Compaoré had accepted a massive IMF loan and instituted a structural adjustment program (largely seen as one of the major causes for the ongoing economic crises in Africa). Compaoré also reversed most of Sankara’s reforms. Not surprisingly this included the insistence that his portrait hang in all public places as well as buying himself a presidential jet.