thetimes.co.uk

It was herd thinking that left the West defenceless against Covid

Matthew Syed

6-8 minutes

Well, who saw that coming, except most of us?

New, tighter restrictions have been imposed on London and the southeast, because of a new strain of the virus. The kind of Christmas many had hoped for has effectively been cancelled. What is certain is that the latest about-turn will be pounced on by critics as yet more evidence of a chronically incompetent government.

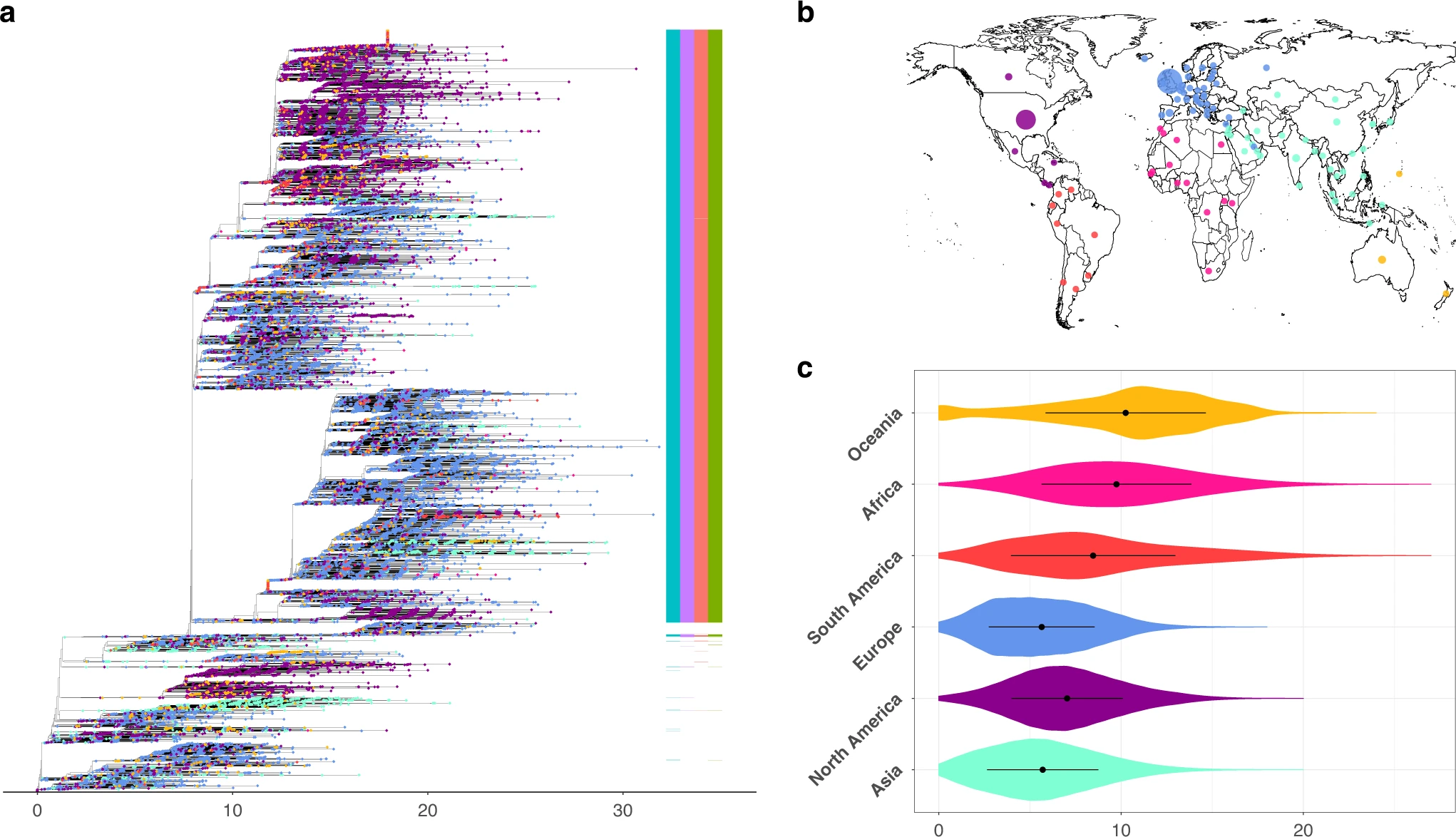

But it might be worth pausing for a moment and taking a fresh look at this tumultuous year. For when you plot the graphs of daily infections in the period since January, you cannot help being struck by the similarity of outcomes between the UK, Italy, France and, to a lesser extent, Germany. It is as if western countries have been looking at what “peer” nations are doing and then dancing to the same tune.

This was true in March, when the UK felt it could no longer go it alone in allowing the virus to spread after Italy, France and Germany had locked down earlier in the month. It was true in early summer, when one western nation opening up put pressure on others to follow suit. It is also the pattern today, with European nations loosening up for Christmas after America had done so for Thanksgiving — with the UK only belatedly changing course.

The point is that the similarity of the graphs across the G7 subset of western nations has less to do with the properties of the pathogen than the psychology of staying close to the herd. It is easier, politically speaking, to fit in with one’s peers.

But this raises a question that will, I think, baffle future historians. Why did western nations largely follow one another when there were vastly better role models? Taiwan has endured few deaths from Covid, and its economy has barely been affected, growing this year by more than 2.5%. By controlling the virus with precision techniques such as tech-enabled contract tracing, it didn’t need to resort to crude lockdowns or cancel national celebrations. And it didn’t have to turn cancer and other patients away from hospitals, because there was always spare capacity to deal with them.

If nothing else, doesn’t this example show that the “trade-offs” that have dominated debate in the West are largely imaginary? With competent governance, there is no trade-off between lives and livelihoods any more than there is between Covid and non-Covid deaths. By controlling transmission, it is possible to keep the economy open, hospitals open and hospitality open, too. The economy and public health are not in conflict; they are synergistic.

The western debate on civil liberties also seems absurd in this context. I mean, would you rather cede a small amount of personal data to help public health authorities identify super-spreaders, as the Taiwanese have done, enabling you to send your children to school, go to work and live your life, or withhold this data and refuse to wear masks, allowing faster spread of the virus, leading to the mass incarceration known as lockdown?

So why didn’t we put every effort into following the success stories in east Asia? I can’t help wondering if it was not for scientific reasons but cultural ones. When I have raised the east Asian experience since March, a common response has been: they are not like us! They are automata who do what they are told! It could never work here! We are individualists!

This is, at best, misleading. Western populations were highly compliant at the start of the pandemic (albeit with a huge drop-off in the UK after the Barnard Castle incident).

Moreover, it is not as if Taiwan is a collectivist paradise. The nation is a vibrant capitalist democracy of 24 million, with a proud tradition of dissent. As the tech magazine Wired put it: “The democracy activists who risked their lives during the martial law era were not renowned for their willingness to accept government orders or preach Confucian social harmony.”

It is true that pre-existing differences played a role in the varying outcomes. East Asia may have benefited from a slightly different genetic strain of the virus striking particular areas, and citizens may have superior natural resistance. They had also had the “benefit” of Sars, which provided the impetus to make better preparations.

But doesn’t this reinforce the point? If Sars had hit America or France, we would have become infinitely more alert to these blasted pathogens. We would have provided acres of coverage. We would have gained a deeper understanding of exponentiality, rather than mocking Asian nations for “overreacting” to a handful of cases. In other words, the reason we didn’t learn from Asia back then is, I suspect, the same as why we failed to learn now.

Indeed, the more I look at the international comparisons, the more I glimpse the influence of psychology. When you look at the similarity of the waves in western nations, you can’t help seeing herd mentality (perhaps “transnational groupthink” is a better phrase) at work. The rate of deaths per million population in France, Italy, Spain, the UK and America is almost identical. But superimpose east Asian nations and you will see a family of graphs utterly different from the West’s — and almost identical with one another.

This explanation carries even more weight when you look at our historical inability to look beyond our cultural horizons. Isn’t the entire postwar history of the West a succession of misadventures based on a catastrophic ignorance of the places in which we were intervening? Think of Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq, to name but three. The academic Amy Chua has described these as “group-blind mistakes of colossal proportions”.

As of today, Taiwan’s death toll is seven, compared with almost 70,000 in the UK. If such a success had occurred in France, there would have been discussion about nothing else. Every meeting in No 10, the Treasury, the Department of Health and Sage would have been about reproducing the success of tech-enhanced tracing, isolating and sophisticated border control. Instead, we have been obsessed with, well, Sweden, the one western nation to have done it a bit differently, but with precious little to teach.

When the full history of Covid is written, other factors will doubtless prove significant in explaining the gulf in outcomes, not least luck. We should also note that western nations led the way on vaccines, thank goodness. But when it comes to containing Covid, it is difficult to resist the conclusion that many of the wealthiest nations failed not because of insufficient capacity but because of narrow horizons. That, at least, is my reading of an otherwise baffling year.

@MatthewSyed